Chasing Invisibility or Do Mosquitoes Go to Galleries?

Fleeting Monuments (Prchavé sousoší) on Letná by Maja Štefančíková, July 31, 2025 foto Olga Krása-Ryabets

The idea of invisibility in art, particularly in live theatre performance, has been a long-standing and deeply rooted interest of mine, one I have explored through both practical and theoretical lenses for many years. My work is equally grounded in perception, especially the cognitive dimension of imagination and its influence on our everyday navigation of urban environments. With this in mind, I was especially intrigued to experience Maja Štefančíková’s new project Fleeting Monuments (Prchavé sousoší), a one-day live performance on July 31, presented alongside the exhibition Radical Tenderness by Iván Argote (on view at Prague’s Rudolfinum until September 7, 2025), which I also decided to visit for additional context. Given Štefančíková’s focus on perception and its overlap with my own artistic focus, I chose to approach the work by creating a kind of mind map of my experience. For this purpose, I attended one of the four components of the performance, at Letná, and later made my way to Argote’s exhibition at the Rudolfinum.

I share my map below, but first, a bit of context. Maja Štefančíková is a Slovak visual artist whose work often balances on the threshold between the visible and the invisible, between presence and absence. She has long been concerned with memory and perception, but always through a lens that refuses the purely personal or psychological. Her pieces tend to take form through performative action, situating the body within broader social and institutional frameworks, labor, systems of power, and the protocols of the art world. What strikes me about her practice is how it oscillates between the intimate (the sensory detail of a single gesture, a pause, a silence) and the systemic (the invisible scaffolding of institutions or histories that shape those gestures). Between the two, space is created for a third thing, crucially, and a deterritorialization is enabled which in turn renders boundaries malleable and allows for alterations in both the private and the social spheres.

The Columbian artist and filmmaker Iván Argote, meanwhile, approaches invisibility and absence from another angle, through monumentality, public memory, and the ways power inscribes itself into urban space. His exhibition Radical Tenderness at the Rudolfinum collects works that question how we inherit symbols of authority, history, and community. Argote has a knack for both dismantling and reimagining, taking something heavy, official, monumental, and rendering it tender, strange, or even invisible. The exhibition includes sculptures, videos, and interventions that all ask us to reconsider what we see, what we overlook, and what remains hidden in plain sight. Against this backdrop, Štefančíková’s one-day performance unfolded like a living counterpart, a fleeting gesture that refused permanence yet echoed Argote’s monumental concerns.

Fleeting Monuments (Prchavé sousoší) on Letná by Maja Štefančíková, July 31, 2025 foto Olga Krása-Ryabets

July’s performance took place across four different locations in the center of Prague. The event began late afternoon with a performative introduction in the Ceremony Hall of the Rudolfinum, before moving outdoors to the site of the former Stalin Monument at Letná, beneath the Metronome (this is the part I attended). About two hours later, the action shifted again to the Marian Column on the Old Town Square, before concluding back in the Rudolfinum Ceremony Hall early evening with a closing sequence. The performers, Jiří N. Jelínek, Radim Klassa, Prokop Košař, Jana Kozubková, Soňa Linhartová, Valentina Mara, Johanka Shmidmajerová, Mária Ševčíková, Barča Šošolíková, Bea Stevens, Alessandra Točoňová and Lukáš Zahy, with musical cooperation by Petra Torkošová, formed a multifaceted ensemble moving between spaces, histories and obscure corners of the mind.

The part I witnessed began beneath the Metronome, in the wide-open expanse where the Stalin Monument once stood. The chosen site already holds something invisible, the ghost of Stalin's gigantic monument and in this way, is marked by absence as much as presence. Viewers gathered loosely around the playing field, with the freedom to move, to come close or retreat, to pass through as if it were another layer of city life. The performers began to move as a collective, their rhythm recalling a flock shifting direction in intuitive, unspoken accord. Each held a sculptor’s mallet and chisel and they struck one tool against the other in a percussive dialogue. While the movements of the performers suggested chiseling away at an enormous slab of invisible stone, the striking of the tools generated a tinkery, crystallic soundscape. Sequences of rhythmic hammering were followed by sudden stillness. In those freezes, silence fell sharply, so total that it carried weight. Then, without apparent signal or immediately detectable pattern, one performer would start again, and the group would pick up the thread, sound and movement rushing back in.

Mind Map

What follows is the mind map I began to build for myself, a way of tracing how the surrounding environment infiltrated the performance, deepening and complicating it in ways that were both strange and delightful. This is a sort of a trajectory my mind took throughout both experiences.

Bugs – In the excellent collection of academic essays on empty spaces in urban areas, Inside-out City (Město naruby: vágní terén, vnitřní periferie a místa mezi místy, ed. Radan Haluzík a kol. 2021), there is an study by Lucie Juřičková and David Storch that imagines the urban environment from the perspective of snails. This returned to me repeatedly during the performance, decentralizing and interjecting my perception of the experience. Throughout the piece I shifted my position, curious about how my vantage point altered the experience. Sitting at one point on the stone benches at the side of the monument, shaded and half-hidden, my eyes slowly moved around the props littering the site: empty plastic bottles, squashed beers cans, cigarette butts, tufts of brittle grass pushing through cracks in the stone. From here I could see the performers as a sort of single organism, their arcs and freezes registering as large-scale patterns interwoven into the debris in a wider shot.

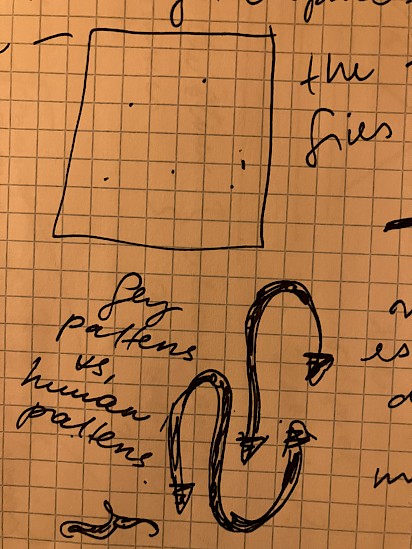

Then something else caught my eye. When the performers stopped in silence, I noticed a group of flies tracing spirals just in front of my bench. Their movements echoed the performers uncannily, tiny versions of the same choreography. For a radiant instant, it seemed obvious that they too were part of the performance, an invisible miniature troupe staging their own dance. Of course the thought dissolved quickly, replaced by reason, but the impression lingered. Later, in the Rudolfinum, I encountered a giant mosquito resting on the wooden steps between Argote’s exhibition rooms, and again I felt that continuity, that the insect world had been following me, stubbornly inscribing itself into both performance and exhibition. What does it mean for our perception when the choreography of flies can momentarily merge with human art-making?

Choreography of flies, drawing and foto Olga Krása-Ryabets |

Giant mosquito visiting Rudolfinum, foto Olga Krása-Ryabets |

Skaters – The Letná site is also a legendary gathering spot for skaters. On that summer afternoon the skate park buzzed with activity: young people trying out tricks, boards clattering against concrete, bursts of laughter and groans of defeat. Sitting on the edge of the skate area, facing the Metronome, I realized how their sounds bled into the performance. The rolling wheels, abrupt flips, and celebratory yelps mingled with the chisels’ percussive rhythm. The result was a layered composition where intentional art and spontaneous city life became indistinguishable.

What interested me was not just the sonic blending, but the parallel choreographies. Skaters too move in a flock of sorts: taking turns, circling, pausing, launching into risky maneuvers, then retreating. Their movements, though unscripted, form patterns born from shared rhythm and collective attention. Watching them alongside Štefančíková’s ensemble highlighted how performance is not a separate category but a network where everyday gestures, falling, recovering, showing off, become part of the aesthetic fabric. For a passerby who knew nothing of the event, the chiseling and the skateboards might have registered as two sides of the same activity: urban bodies in motion, testing limits of balance, rhythm, and space.

Radical Tenderness at Rudolfinum by Iván Argote, foto Olga Krása-Ryabets

Invisibility – I circle back here to my key point of interest: invisibility. From Harry Potter’s cloak to Yoko Ono’s Instruction Pieces, invisibility has long fascinated art and imagination. In my own work, Invisible Theatre for No One (2024), I staged soundscapes by moving around my bedroom while the audience listened from behind a closed door. They could not see, only hear and in that absence, imagination filled in the rest.

In Štefančíková’s performance, invisibility emerged less as an object and more as a gesture. It was as if the group were building a monument we could not see, an edifice made of silence, sound, and fleeting movement. This resonated with Argote’s work, especially Who?, where only two giant bronze feet remain of a once-whole statue, prompting us to imagine the absent body. The Letná site itself is haunted by absence: the Stalin Monument, once the largest statue of him in the world, now gone, leaving behind only its pedestal and the weight of history. Watching the movements of the group, I felt the performers conjuring a ghost monument, fragile and invisible, layered onto the absent Stalin. The history of the destruction of the statue, in 1962, is as rife with complications and dark shadows as the history of its construction in 1955. According to certain urban legends, the enormous stone head of the soviet dictator is still hidden somewhere in Prague.

At times this connection to history risked being too literal. I found the piece most powerful not when it echoed the Stalin monument directly, but when it unsettled perception in subtler ways: in the overlap of chisels and skateboards, in the merging of dancers and flies. These moments revealed how performance can render the invisible visible, not by conjuring images of the past, but by shifting the frame of the present so that patterns and resonances emerge where we might not otherwise notice them.

I won’t go into Argote’s exhibition in more detail here, but certain works resonated deeply with these thoughts. The room with only the bronze feet, the mirrors that rendered horse riders invisible, and the video about an imaginary word used to construct an imaginary square, all seemed to echo what I had experienced outside. At its core, what I witnessed across performance and exhibition felt like the bare bones of what any art, and especially any live performance, makes possible: the chance to construct and briefly inhabit an imaginary world. And it is precisely that inhabiting, however short-lived, that makes the return to the “real” world so poignant, sharp and alive.

Olga Krása-Ryabets

Radical Tenderness at Rudolfinum by Iván Argote, foto Olga Krása-Ryabets